Press Kit

Click on the link at the bottom of this page for a complete .pdf media kit for Donis’ newest release, Hell With the Lid Blown Off (June 2014). The kit contains a large cover, a blurb, ordering information, Donis’ biography and head shot, information about Donis’ six previous Alafair Tucker novels, and information about Poisoned Pen Press.

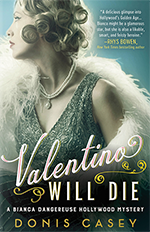

ANY information on this website may be used for publicity. Biographical information is on this page, as is an interview with the author. For a larger picture of Donis, click on the image ot the right, then right click to print, or you are welcome to use any of the pictures from the Gallery page. For pictures of the book covers, go to the Gallery page, or to the “About this book” pages under the cover images at right, where a larger image of the cover can be found. Right click on the image to print. You may also click on “Order”, under the cover images at right, which will take you to the Poisoned Pen Press web site, where you may print off a large image of the book cover.

Hell_With_the_Lid_Blown_Off_Media_Kit

The “Gallery” page contains links to photos I have uploaded from some of my book tours and appearances, as well as a two-minute movie of Yours Truly reading a bit from The Sky Took Him.

The “Truth or Fiction” page contains information in depth about how the books came to be, the characters in the books, and which parts of the stories are taken from real events and which are pure fiction.

REVIEW FROM “WOODSTOCK’S BLOG” (www.journalscape.com/woodstock)

“…Alafair Tucker is the busy mother of ten living children, running the domestic side of a successful farm and sharing a loving supportive relationship with her husband, children, in-laws and neighbors. In each of the three books in Casey’s series, one of Alafair’s children has been threatened, and although she has no position in law enforcement, she has played a major role in bringing a criminal to justice. Casey has an enjoyable, believable combination of historical and medium boiled mystery amateur protagonist. Books like this are hard to find!”

BIOGRAPHY

DONIS CASEY was born and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma. A third generation Oklahoman, she and her siblings grew up among their aunts and uncles, cousins, grandparents and great-grandparents on farms and in small towns, where they learned the love of family and independent spirit that characterizes the population of that pioneering state. Donis graduated from the University of Tulsa with a degree in English, and earned a Master’s degree in Library Science from Oklahoma University. After teaching school for a short time, she enjoyed a career as an academic librarian, working for many years at the University of Oklahoma and at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona.

Donis left academia in 1988 to start a Scottish import gift shop in downtown Tempe. After more than a decade as an entrepreneur, she decided to devote herself full-time to writing. The Old Buzzard Had It Coming is her first book. For the past twenty years, Donis has lived in Tempe, AZ, with her husband.

CONVERSATIONs WITH DONIS

The following interview appeared in November of 2014 on the website of Barbara Fass Leavy.

AN OKLAHOMA FAMILY; DONIS CASEY’S ALAFAIR TUCKER MYSTERY SERIES

Introduction by Barbara Leavy

Whether it is called a melting pot or a mosaic, the United States cannot be pinned down to a single culture or even a few cultures. The native tribes that lived here before the European settlers came were themselves diverse in their beliefs and their practices. Waves of immigrants were and are drawn to different parts of the country, sometimes because the geography reminds them of the lands they left behind. The physical landscapes of the United States are studies in contrast and there is no possibility that travelers who toured the country and visited Santa Fe, New Mexico could think they were in Bar Harbor, Maine. But people who live on either coast sometimes patronizingly think those states in between are without sophistication, even though some of the finest universities exist there and their great writers and artists would constitute a list too long so present here.

A mystery writer who lives in one part of the United States and writes about another often might just as well be setting a story in a foreign land. This is also true of a literary critic who wants to study a book in the context of the culture that is its setting. For me, the London of Ruth Rendell is far more familiar than the Appalachia of Sharyn McCrumb. When I decided to write a full-length study of a crime writer, it was McCrumb and what are called her ballad books that I decided to write about.

I had taught, read, and re-read over and over The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter. The lyricism of its prose and the pieces of folklore I recognized that settlers brought with them from the British Isles captured me. Folklore in stories and music was what I grew up on and my literary studies allowed me to pursue what I loved. I think that The Ballad of Frankie Silver is a masterpiece of American literature, a heartbreaking story that combines the history of the past with the families McCrumb readers can follow through her Spencer Arrowood series.

At some point, however, I began to feel unable to analyze this series. What was culture-specific about the books eluded me. The people in them did not live next door or down the block. Their lives were shaped by different traditions and different histories. Stereotypes existed about them and it was clearly one of McCrumb’s purposes to dispel the mistaken perceptions of Appalachia. The image of L’il Abner and Daisy Mae might come to mind but most of the people in the area do not regularly go barefoot. In McCrumb’s series, the Hatfields and the McCoys seem reflected in the Harkryder family, but most of the people in Appalachia are not involved in family feuds and are not what some refer to as white trash. One of McCrumb’s characters remarks that some groups are defined by their best people, others by their worst.

So I gave up the idea of writing about Sharyn McCrumb’s ballad books, even though McCrumb herself graciously sent me a bibliography of books about Appalachia that might clear my path.

There was, however, a character in She Walks These Hills that I immediately identified with. An instructor and graduate student in an Eastern college, he is writing a doctoral dissertation on an Indian captivity story about a white woman settler kidnapped by Indians who made her way about two hundred miles back to her people. I have always loved these captivity tales epitomized in the classic film, The Searchers. The graduate student decides his dissertation would be improved by a dose of reality and he would follow the captive’s footsteps. Having only gone to summer camp, he had never hiked, so he did not know that the books he put in his backpack would be such a handicap that he would dispose of them—and most of whatever else he thought he needed to buy in an outdoor sports shop before setting off on his quest.

He is an important character in a very powerful novel, but his misadventures also prove humorous. McCrumb is not only lyrical in her writing but at times is side-splittingly funny. What I came to realize is that this academic misfit on the rugged trail would be me if I tried a serious cultural study of a mystery set in Appalachia—or in many other places.

As I interview PPP authors about their books, I tend to stress how I connect to their stories and themes. What I have described above is quite the opposite. It depicts the cultural gap between me and the stories that have nonetheless made an enormous impression on me. Throughout reading them, I am often struck by unfamiliarity rather than familiarity. I am therefore very pleased to have Donis Casey talk about her life, the writing that emerges from or contrasts with it, and about the Oklahoma in which her Alafair Tucker series is set. In reading the responses to the questions I asked, you will readily find Donis the storyteller.

Donis Casey on Sharyn McCrumb and the culture in her Appalachian series.

It’s interesting that you mentioned Sharyn McCrumb’s books, in particular She Walks These Hills. McCrumb put her finger on something that I’ve observed many times, especially among Appalachian and Native folks of my parents’ and grandparents’ generations; they had a different perception of reality than is generally accepted in the Western world today. I can’t tell you how many “ghost” stories I’ve heard from my elders and elders-in-law. In several of my books I included some small incident that we might think uncanny or otherworldly. Nothing too blatant, but presented matter-of-factly. I had a reader ask me once how come Alafair accepts such things without question, since she is obviously such a practical person. I replied that her practicality is exactly why she doesn’t question her own senses. If I saw an apparition, or heard a voice when no one is about, I might question my own sanity. In my experience, people of Alafair’s time and place would simply say “I saw a ghost” (actually, she’d say “I saw a haint”) and that would be that. No one would try to talk her out of it, and if they did she wouldn’t have it. I would not be so arrogant as to question her experience, either. Maybe she can see a larger spectrum of light than I can or hear subsonic vibrations. What do I know about the nature of reality?

Tell us about yourself.

I am a third-generation Oklahoman, born and raised in Tulsa by fairly well-to-do and well-educated parents. My parents read to us constantly, and wanted all of us to study some form of the arts, especially my father. So we were big into literature, music, and art in my house when I was growing up. I spent most of my working life as an English teacher and an academic librarian, and also owned a small business. I was always fairly successful in my career endeavors, but after I reached a certain age I realized that I had never been all that happy with them, so I asked myself, “Donis, what do you really enjoy?” The answer was storytelling. After a discussion with my ever-encouraging husband, I sold off my business and went home to write a book.

You have blogged about your family’s history, which seems so much a part of the history of the U.S. Can you describe that to us? In what way did your family contribute to the specific growth and development of Oklahoma? How did they come to settle there?

You are correct about my family history being very much a part of the history of the U.S. When I was a child, my mother told me that we are “Scots-Irish and Indian” and we had been here a long time. I was disappointed, because I wanted to be descended from recent immigrants who came to the U.S. through Ellis Island from some exotic clime like Turkey or Italy or Australia. But after I grew up and learned a little bit I began to realize that my background is actually pretty interesting. I descend from the Scots-Irish who were encouraged by the early Colonial governments to come to the Colonies from Ulster and settle. They were given free land on the Western frontiers if they could clear it and live on it for two years. The thought was that the Scots-Irish were tough enough to act as a buffer between the Natives and the English.

I’ve told this story before, but it’s illustrative. Many years ago, when I was on a plane flying from New York to Dublin, I got into a conversation with my seatmate, a woman several years older than I was at the time. We were chatting pleasantly when out of nowhere she asked, “Where are you from?” (I expect my accent roused her curiosity). I said, “Tulsa, Oklahoma,” and she laughed. “What a place to be from!” she said. Oh, I never forgot that, you can be sure. No matter how mundane you think your history and native place is, to most of the world it’s wildly exotic.

I heard many a tale about all branches of my family from all of my grandparents, but until I actually started researching my own genealogy I didn’t know how much was true and how much was embellished, since my grandparents were great embellishers. I was amazed. I have not been able to find but one ancestor on any side who came to this country after the Revolutionary War, and he came over from Scotland in 1820. My original Casey ancestor, Abner, emigrated from Tyrone in 1723 and ended up in South Carolina. All ten of his sons fought in the Revolution on the American side. Two were with Francis Marion. One was a general and later a Congressman. Several fought at Cowpens, including my direct ancestor. He married a woman named Polly Wayne, the sister of the Continental Army general Mad Anthony Wayne. I have a forefather who was sent over here during the war as a British soldier. He deserted and was hidden for the duration by an Irish-born farmer, whose daughter he eventually married.

My father’s mother was a Morgan from Kentucky, descended from one Morgan Morgan from Glamorgan, who came to this country in 1700 and was one of the first settlers in South Carolina. By the time of the Revolution much of that family had already moved out to the hinterlands of Kentucky. My great-aunt told us that they were “tall, dark, men, who came down out of the hills with their long rifles to help the cause, then faded back into the wilderness when the fight was over.” Daniel Morgan was also a brother to my direct ancestor.

After the war ended, my restless relatives began to move West. My father’s paternal side and both of my mother’s sides were pioneer settlers in the Ozark mountains of northern Arkansas and southern Missouri. That’s where some of them met and intermingled with a few Western Cherokees who had slipped off into the Ozarks when they were being moved to the Indian Territories in the late 1820s on the Trail of Tears. The Arkansas-Missouri border was particularly bloody during the Civil War. I have ancestors who fought with the Union as well as ancestors who fought with the Confederacy. In one case, a paternal grandfather and a maternal grandfather were at the same battle on opposite sides. Only one of my personal ancestors moved to Oklahoma before 1910.

According to my grandmother, my great-grandfather Morgan owned a large, productive farm in the hills of Kentucky but decided to move his very large family to Oklahoma in 1910 “because it was flat.” He bought a farm outside of Boynton, Oklahoma from a Creek woman named Sarah Fishinghawk. I spent a lot of time on that farm when I was a kid. It’s still owned by my father’s cousin, and is the template for the farm I created for Alafair and Shaw. My grandfather Casey had enough Cherokee blood to qualify for tribal rights, so he moved to Oklahoma before statehood and received an allotment. By the time he met my grandmother, he had sold the land and bought a building on the main street in Boynton. He rented out office space in the building and operated a barber shop there for years.

My mother’s parents were farmers from Mulberry, Arkansas. Her father bought a farm outside of Boynton when my mother was 10. In 1945 she was a soda jerk at Williams Drug in Boynton when my father, newly returned from the Pacific, walked in dressed in his Marine uniform. And the rest is history. Many of the stories I use in my books are from my husband’s family history (and lore). He has a longer Oklahoma background than mine. His three-greats grandfather came to the Indian Territory in the 1870s from Illinois. The thinking was that he was running from something, since until 1907 the IT was not the United States and most of the Whites who came in did so to escape the law. Have you read True Grit? The United States had treaties with the various IT tribes, which allowed U.S. Marshals based in Texas and Arkansas to pursue fugitives into the Territories. What we do know for sure about Don’s ancestor is that he married a Choctaw woman, which was the only way a White man could acquire property in the IT at that time. This is the basis for the story in my book Crying Blood. Don’s people are very colorful. Between his cowboys and Indians and my hill folk and Indians I ended up with a book length genealogy packed with stories from the French and Indian wars, the Revolution, the Civil War, World Wars I and II, ambushes, murders, adoptions, divorces and adultery — settlers and Indians, massacres, poisonings, axings, shootings, drownings, and smashing people in the head with beer bottles. I don’t really need to make much up. Reality is more amazing than anything I could come up with.

What about your series is specifically Oklahoman? Could it take place in Nebraska or Kansas? In Wyoming or Colorado?

I hear often from readers all over the world who tell me that there are things about Alafair’s life on the farm that reminds them of tales they’ve heard from their grandparents. Life on a family farm during that period was similar wherever one lived. However, Oklahoma was a place like no other in the world in the 1910s. It was incredibly rich – there was oil and cattle and land almost for the taking. It was poor and lawless at the same time, because people were coming from all over the world with nothing to make their fortunes however they could. It was still the Wild West, and yet because of the money, it was the most cutting edge modern in the cities. Many cities were brand-new at statehood, because they sprang up overnight after the Land Runs.

It was an amazing racial mixture for that time. It had been the Indian Territory, after all. And the Oklahoma Indians were not like the Indians in other parts of the country at that time. They had run their own country for seventy-five years, and had their own Tribal congresses, newpapers, colleges and schools, and some large plantations.They were used to being in charge of themselves, and they didn’t much appreciate all these Whites flooding in from other parts of the country with their insulting ideas about the native people. From the beginning, Oklahoma Indians have been much more integrated with the general society and much more self-determining than anywhere else in the U.S.

Oklahoma also had (and still has) many Black towns, as well. These towns were founded and run by slaves who had escaped into the Nations before the Civil War, or by freed slaves leaving the south after the war. These were also people who had completely run their own show for years, and again, all the Whites coming in with their unsavory racial attitudes didn’t sit very well. Right after Statehood, Oklahoma was the most socialist state in the Union. A larger portion of the electorate in Oklahoma voted for Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs in 1916 than any other state. The labor movement was very big there, and they didn’t cotton to the U.S. getting involved in the “rich man’s war” in 1917. There were several draft riots around the state in 1917. Which is not to say that after the U.S. entered World War 1 there wasn’t as much rabid patriotism there as there was in the rest of the country. It’s a great place for a mystery series. Lots of opportunity for murder.

When and how did the Alafair Tucker series come to you? How much of yourself and/or your family is in Alafair and hers?

I wanted to write a series patterned after Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael Mysteries, which contain everything I love about historical novels plus very clever and twisty mysteries. So I set out to create relatively short books with a great deal of humanity, a warm central character, a detailed evocation of the time and place, and as surprising and morally ambiguous a mystery as I can manage. But in order to make the world as real as I could, I “wrote what I know.” Many of the details of farm life I learned from my mother, who grew up on a subsistence farm during the depression, such as using kerosine-soaked corn cobs to start a fire. The characters began as composites of family members, but they are their own people, now.

All during my childhood, my mother made the most delicious pear preserves from the sweet, hard pears from the tree in her back yard. I have never before or since tasted anything like it. When I heard that the tree had died, my first thought was that no one will ever taste those preserves again, because nobody cooks like that any more. This made me think of my grandfather, who buttered his green onions before he ate them. I decided that I wanted to take the opportunity to try and evoke not just the events of the time, but the smells, the tastes, the sound, the hot and cold of it — the daily one-foot-in-front-of-the-other life of a farm wife with ten children. I also was very concerned to preserve something of the language as well as the way of life. The dialect I love so is disappearing. My grandparents always sounded amused when they spoke. The vocabulary was absolutely Elizabethan. When my grandmother went to garden, she drew on her gauntlets and hunkered down over yonder to pull yarbs and slip them in her poke. A gauntlet is a heavy glove, and if you were born in Kentucky in 1893, you pronounced it “GANT-let.”

I’m fairly well educated myself, and I grew up determined to speak English in as standard a fashion as I could. My parents were college educated, but their parents and older relatives weren’t, so I grew up around country people. My most-schooled grandparent graduated from the eighth grade, which was as far as most people in that time and place could go. One grandparent only got as far as the third grade. But just because you didn’t get very far in school doesn’t mean you aren’t smart. Michael Caine, who is Cockney, once said that people too often judge your intelligence by your accent. One of my uncles walked into our house one day and said, “What in the cat hair is going on?” How could I let that fade into oblivion?

Can you imagine yourself living Alafair’s life? If so, how? If not really, how does this affect your series?

I wonder sometimes if readers think I have the same values and ideas as my character Alafair. I myself wondered how like their characters other authors are until I actually started writing fiction. Now I think the answer often is, “not even close.” I just wrote a scene in which one of my characters does something that he absolutely believes is right, and in the context of the story, he is right to do it . But I, Donis Ann Casey, would NEVER consider the action justified. One of the joys and perhaps one of the great challenges of writing is that you can explore lives, places, times, people, attitudes that are entirely different from your own–walk in their shoes, as it were. Alafair leads a life that couldn’t be less like mine, nor does she believe the things I do. And yet I know her intimately. I grew up around her world and loved a lot of people who were just like her. I read an interview with Salmon Rushdie in which he said he didn’t have to be religious himself in order to understand quite well how a religious person thinks, and not only to understand him, but have great admiration for him. That’s how I am with Alafair.

When did you decide you wanted to become a writer? What books influenced you most?

I don’t know when I decided to become a writer. I’ve written stories since I could hold a pencil in my fist. Perhaps it’s because my parents read to me from the cradle, or because I come from such a long line of tale-tellers. One of my grandmothers used to keep us fascinated for hours on end with her stories of life in the Kentucky mountains. Toward the end of my grandmother’s life, one of my sisters asked her how much of what she had told us was true and she replied, “Well…some of it.” So the truth is I didn’t decide to become a writer. I’ll quote the Achilles character in the movie Troy: “I didn’t choose this life. I was born and this is what I am.”

The first book I remember reading over and over on my own was Lucy Fitch Perkins’ The Chinese Twins. I read all her Twins books. I loved the foreign settings and imagining what it was like for those children to grow up in such unfamiliar societies. When I was in middle school, I went through a science fiction phase. My favorite books then and now are historicals.–and I still love any book that allows me to live in an exotic place and/or time for the duration. When I was a teenager I read Beau Geste seven times in a row.

Have you had any other careers? What schools did you go to? Did they or any particular teacher have a strong influence on your writing and/or your decision to be a writer?

I started my professional life as a middle-school English teacher, then became an academic librarian with a specialty in U.S. Government publication, which is what I did (in Texas and at the University of Oklahoma and Arizona State University) for most of my working life. When I had finally had enough of academia I started a small Celtic gift shop in Tempe which I ran for more than a decade. I have a B.S. in English Education from University of Tulsa, one of the world’s top schools for Petroleum Engineering. Rather like getting a humanities degree from MIT. I also have an MLS from the University of Oklahoma and worked toward a PhD in English with a concentration on the history of the language, but quit before I finished. I had some very good teachers in high school who encouraged me and told me I was a good writer, but I would have written anyway.

Were you an avid reader of mysteries? Whom did you read? Who affected your sense of the genre and the kind of mysteries you would write?

I was an eclectic reader in my youth and still am. I’ll read just about any type of literature, whether it’s fiction or non-fiction, if it catches my fancy. Historical fiction was my first love, though. If I were to pick my ten favorite books, most of them would be historical. One writer of historical fiction whom I really loved was Edith Pargeter, a prolific English novelist. She wrote several historical novels set in England and Wales in the middle ages, and her poetic language, style, and evocation of the times really spoke to me. When I finally ran out of Pargeter historicals I was very sad. But a little research showed that she also wrote a historical mystery series under the name Ellis Peters, and that is how I ended up reading all twenty of her Cadfael novels. That was the first mystery series that really captured me. Since then there have been many other mystery writers whose work I admire. I like Louise Penny, Lee Child, Sara Paretsky. Sandra Dallas, Sharyn McCrumb, Deborah Crombie, Tim Hallinan, Naomi Hirahara . . . many more. Too many, and as you can see, an eclectic bunch. But all those I mentioned have a very strong sense of place and well-developed main characters.

In your most recent and highly acclaimed book,Hell with the Lid Blown Off, the mother of the murder victim, a truly despicable person, wonders if she had failed to love him enough. In a nature-nurture dichotomy, do you favor nurture? Alafair is certainly a nurturing mother.

In my first book, The Old Buzzard Had It Coming, the victim is also a horrible person, as you might guess. But his son is honest, caring, and rather innocent of the ways of the world. I have Alafair wonder how it is that you can put two people in exactly the same situation and one will crumble while the other heroically rises to the occasion. Both Jubal and Harley (the Old Buzzard) blame other people for all their problems. I do believe in nurture, but I also think that once a person is grown, her life is in her own hands. Once you are out of their control, using the parents as an excuse for everything wrong in one’s life is unproductive in the extreme. I must say that thus far Alafair has been extremely lucky with her kids. She knows it, too. Who knows if it’ll last?

Your bad guys remind me of Judd in the musical Oklahoma. Is something about life in Oklahoma that would produce a type like Judd. Is it not just parents who nurture but a much wider environment?

Are they bad? Or are they just angry and paranoid? Nobody is all bad, of course. Early on in Oklahoma and much of the West and Southwest, places that were homesteaded and settled by pioneers, there was basically no (white) society to judge your behavior. You and your family were on your own. You didn’t expect help and you knew that if you didn’t grow it, make it, shoot it or take it yourself, you didn’t have it. And if you build a life that way, completely self-reliant, you don’t like it when law or government or society grows up around you and tries to tell you how to act. That attitude is passed down to your children and grandchildren, and still prevails in a lot of places across the Big Middle.

Why did you move out of Oklahoma?

In the ’80s, I was head of the Government Documents Department at the University of Oklahoma Library, when I was “head-hunted” by Arizona State University to take over their Documents Department. Government publications was an uncommon specialty then. My husband was all for the move, so we did it. At the time, Arizona was in better financial shape than Oklahoma, and ASU paid much more than OU. Times have changed.

One might think that physically Arizona is not that different from Oklahoma and West Texas, but one would be wrong. Oklahoma is plains and rolling hills, and Arizona is quite mountainous. And I didn’t know the name of one native plant out here. I felt like we had moved to the moon. However, having grown up in Tornado Alley, I generally love the weather here. We have no relatives living near us, and I foresee that eventually one or the other of us will be on his or her own and will have to move closer to kin in Missouri or Colorado. But I doubt if I’ll go back to Oklahoma permanently.

For a charming short piece on “Mrs. Casey’s Cafe” click on http://www.poisonedpenpress.com/mrs-caseys-cafe/

And one more Q&A from early on in my career as Alafair’s biographer.

Q: Where did you come up with those titles?

A: I went through several titles before I landed on The Old Buzzard Had It Coming. Since the book takes place in Oklahoma in the dead of the winter of 1912, I first tried to find a title with the word “cold” in it, as in “cold-blooded murder”, but I wanted something ethnic. At first I called it He Had It Coming, since the victim is quite a horrible person. Then one day, my mother described a man who lived in her apartment complex as an “old buzzard”. aha!

As for Hornswoggled, that book was originally called Cruel as Knives, which is something Alice said when she was a child. But, again, when it came time to publish, I wanted something that was a little bit more “country”, and that conveyed the web of deception and misdirection that surrounds the murder of the unfortunate Lousie Kelley. I must have considered every word in the English language that is a synonym of “fooled”. My thesaurus was smoking, but I couldn’t come up with just the right term, until my beloved husband Don literally dreamed the word “hornswoggled”, which fits perfectly, and thus saved my sanity.

Q: Why did you decide to write mysteries?

A: I had always intended to write a mystery. After I created Alafair and her family, it seemed natural to write a series of mysteries, each of which will be based around one of Alafair’s nine (and later, ten) children. The series will move through the early 20th Century as the kids grow up. This gives me the opportunity to involve Alafair in the rather scary enterprise of shepherding her family through an uncertain future. In fact, the beginning of the 10th Century was just about as frightening as the beginning of the 21st Century is turning out to be. Nobody knew what was going to happen.

Q: You write a lot about Alafair’s daily life on the farm. Did you do a lot of research in order to make the story so authentic?

A: Yes, I wanted to try and evoke not just the events of the time, but the smells, the tastes, the sounds, the hot and cold of it, the daily one-foot-in-front-of-the-other life of a farm wife with several children. I am an ex-librarian, so I did a lot of library research, but really most of the detail in the books comes from oral histories that I took from my mother, my in-laws, and other relatives. You can get a lot of information from books, but there’s nothing like living memory for picking up the minutiae of daily life.

Q: You mentioned that some incidents in the books are based on real happenings. How much of the stories are fact and how much are fiction?

A: The books are mostly fiction, though they are scattered through with real incidents. On my website, I have a page entitled Truth or Fiction, in which I tell which parts of the books are based on actual happenings.

Q: Is the character of Alafair based on anyone you really knew?

A: Alafair is a composite. I would say that she is half my mother, half my mother-in-law, and half myself, along with a good bit of several other women who had an effect on me. I realize this makes her more than a woman-and-a-half, but for Alafair, that’s about right. I came of age in the feminist era, and until recently, I don’t think I really appreciated the strength of character it took to live a woman’s life in the past. Also, Alafair and her kind had something that one doesn’t see much of any more — a kind of deep empathy and compassion that is also hard as nails.

Q: What about the old buzzard? Based on a real person?

A: I’ll never tell.

Q: You have no children of your own. Why did you make your protagonist a mother of so many?

A: Once upon a time, while in a grocery store, I saw a woman being terrorized by her small child. My thought on observing this pitiful scene was that my mother would have jerked my arm out of its socket if I had behaved like that in public. I know how to mother better than that poor woman, I thought, and I don’t even have any children. It’s not so easy for young parents any more. People don’t grow up in big family groups like they did in Alafair’s day. I have much younger siblings and observed expert parenting first hand, and had plenty of opportunity to be a practice parent. I was also an elementary school teacher for a while, as well, which was enlightening.

More Places to Go

Donis on Facebook

Type M for Murder