My Tell Me Your Story guest for February is the acclaimed Anne Canadeo, author of over forty books, including the Black Sheep & Company Mysteries, and the bestselling Cape Light and Angel Island novels, written under the pen name, Katherine Spencer. Away from her desk, Anne is a down and dirty gardener, a creative cook and ardent dog lover. Active in her community, she been recognized by New York State for her volunteer service with the homeless and a food outreach. Anne lives on Long Island with her husband and their dog, Leo. Her first historical mystery,More Than You Know, a suspenseful tale set against the backdrop of New York City in the dynamic post-war era, has just been published. I loved it! Check out Anne’s website at https://annecanadeo.com. She loves to hear from readers!

Writing Lessons

Anne Canadeo

Ask me to write about a character in one of my books, or even a real life person, and I’ll tap out a pile of pages in no time. Write about myself? Trace the steps that led to this point in my career? That’s a tougher assignment.

Why I became a writer is simple; I always had a knack for making up stories and poems, well before I was able to write them down. Poems, mainly, would bubble up in my head, and I’d recite them by heart at the supper table.

Despite this precocious talent, reading was an impenetrable code I could not crack. A hospital stay derailed me a few months during first grade, then the family moved in the middle of the school year. The main reason was dyslexia, which didn’t have a name yet except for, “Guess she’s not that bright.” Enter, a reading specialist, Mrs. Wilder—patient, kind, encouraging—with wire-rimmed glasses and white hair as soft as her voice. Once the flip was switched, I was rarely seen without a book in hand.

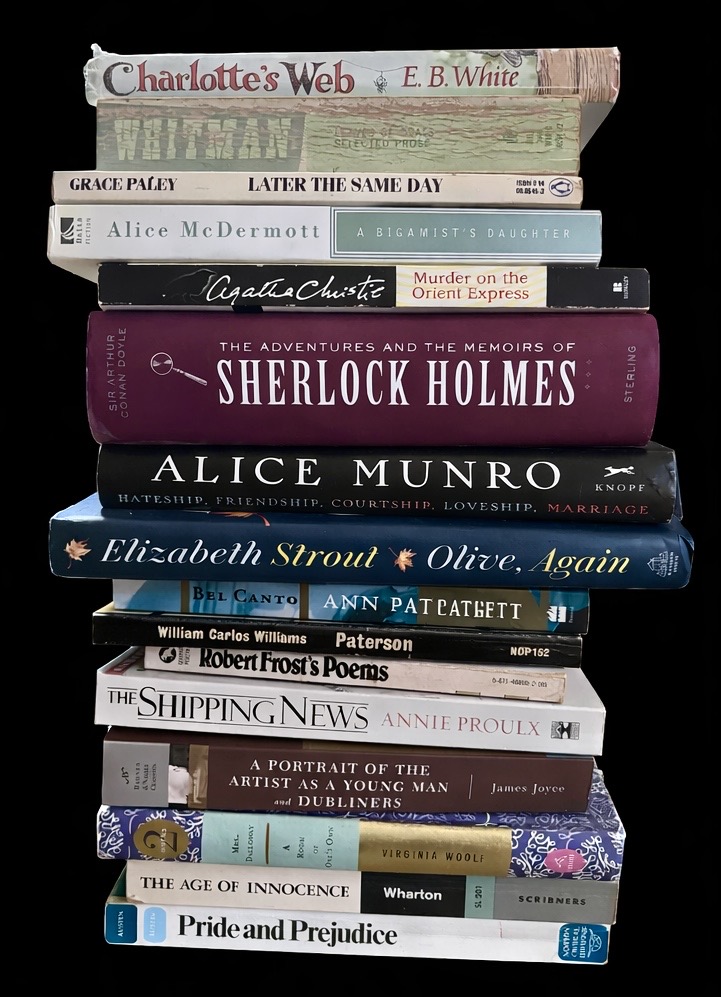

About this time, my father read aloud from Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White, one chapter a night. I identified completely with poor, bewildered Wilbur, dropped into a strange, new world, isolated and unhappy. At age six, I didn’t fully understand Charlotte’s death. But White’s choice of truth over a sugar-coated ending was an important lesson for a someday author. The simple, elegant prose, and clear-eyed realism made a lasting impression and held up a model narrative voice.

This was my first writing lesson and the first book I placed on a special shelf in my head.

My need to read required frequent visits to the library. We lived in a small town where a limited collection was set up on the second floor of an old wooden building with creaky stairs and distinctive smell. There were large, modern libraries nearby, but both my parents worked and I could walk to this one after school.

While friends were at camp, I hung out with Emily Bronte and Charles Dickens. I bravely jumped into a churning sea of language that rolled over my head. I’d bob up for air and keep going. “I am an observer of human nature, sir,” declared Mr. Pickwick. The words rang true to me.

I loved mysteries, a hint I’d write them someday? Nancy Drew and even Encyclopedia Brown bored me. I went straight for Sherlock Holmes, fascinated by his powers of deduction, discerning a suspect’s height, weight, and even eye color from a mere footprint. I wanted the type of hat he wore, with ear flaps, for Christmas, but it couldn’t be found. Or so my mother said.

At a certain point, I bypassed the children’s section and choose books from the adult shelves, which concerned the town librarian, Mrs. Lynch. I’ll stop here to assure you I think the world of librarians, champions of literacy, fighting at the front lines of the current attacks on free speech. They deserve our gratitude, respect and support.

Mrs. Lynch, may she rest in peace, was a busybody. She’d call my mother to ask if I was allowed to check out books I’d chosen, like, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers. A master class in empathy; deeply moving, but never maudlin in its portrayal of marginalized souls, on the fringes of community. My mother said I could read that book, and others that seemed, “too old” for me.

In college, I discovered the Transcendentalists—Emerson, Thoreau and Whitman, as well as Emily Dickenson. Leaves of Grass was a revelation. I’m still moved by the poet’s descriptions of everyday people and his genius for expressing the connections of all of humanity, and the natural world. The essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson were a touchstone, and his mighty pronouncements of self-reliance steeled my spine on weekend visits home, where I was coaxed and badgered about applying to law school, or aiming for some other high status career. One more practical than becoming a writer.

Despite what my parents feared, I wasn’t bold enough to dive off that high board. My plan was an academic life, teaching literature at a college and composing poetry in my spare time. First step, publishing poems would help me get into a good graduate school.

Back to the library, to the section that held literary journals, shelved alphabetically. I pulled out the first three and sent my best work. Weeks later, a letter arrived from Bitterroot International Poetry Journal, the least known, with a circulation that was likely smaller than the number of letters in its masthead.

Of course, I was thrilled. A stunning victory! I was a published author at age twenty. This writing business wasn’t so hard after all, I decided. A combination of naivety, beginner’s luck and bravado is a dangerous thing. That was a lesson that took me awhile to learn.

Woman plans and God laughs. My plans for graduate school and academia were upended by marrying my college boyfriend right after graduation. He’d taken a job in the hotel industry, and we lived in different places about six months at a time—Colorado, Minnesota and the Bahamas.

This was a different kind of writing lesson but invaluable for a young person who’d rarely left New York state. I found a pamphlet that advertised freelance writing opportunities—probably in a library?—and got a job for a newsletter called Environment Reporter published by the Bureau of National Affairs in Washington, D.C.. I lied on my application, claiming I’d studied Environmental Science. My roommate had, so I persuaded myself that counted.

The assignments required researching tedious laws about air pollution and the disposal of toxic waste. But I got paid for writing and have the stub from my first check somewhere. We moved from Denver to Eden Prairie and I took my slim resume and clips to a community newspaper, and got a job as a reporter.

I loved driving around the rural area, attending school board and city council meetings, interviewing a hero fire fighter, or a woman who’d seen a UFO. I learned how to write fast for a deadline, to research odd subjects (this was pre-internet) and how to ask questions and really listen to the answers.

One day, my boss picked up my copy along with a big, black marker. “This is how I edit your work.” She slashed most of the first page, which I’d labored over. Then circled other bits and drew Xs and arrows in different directions. When she was done, the article had boiled down from three pages to one. A brutal, brief lesson on where to start, and how to edit ruthlessly.

I was still writing poetry. “Not bad, send more,” the scribble at the bottom of a form rejection from The New Yorker read. I was elated…but had sent my very best poems and had no more.

We returned East. I didn’t have the fire in the belly needed for real journalism, not in New York City. A recession was raging. Job hunting was like the last round of musical chairs, which I’d never been good at. I’d tabled my grad school—college professor plan and got a notion I’d like to work in publishing. I knew nothing about it, except that I’d be making books. Which sounded ideal.

I found a job as an assistant editor for a small, privately owned company, which I quickly realized was the bottom feeder of the book world. I planned to look for something better while working there. When two editors above me left to start a magazine, I was abruptly promoted—more like propelled—into the driver’s seat, suddenly in charge of a production schedule of eight titles a month. I’d also been accepted into the master’s program at Columbia University and was allowed to fit my work hours around classes.

Splitting my days between lectures about Milton’s Paradise Lost and running the McFadden Romane line, I felt like Alice, jumping back and forth through the Looking Glass. Around this time, writing lessons came from the work of Virginia Woolf, Jane Austen and Edith Wharton, geniuses in the art of observation, the depiction of social classes and the intricate dance of relationships. Austen’s subtle wit was icing on the cake. Toni Morrison had recently published Song of Solomon, which captivated me.

I completed my degree, which led to a job at Simon & Schuster. I was accepted into the Ph D. program, but the glittering world of commerce had me in its clutches. I still wanted to write and had moved on from poetry to fiction, my spare time scarce. I switched jobs again, hired at Dell Publishing as a senior editor in charge of profitable line of women’s fiction, managing other editors, freelancers and a list of authors. I worked day and night, in the office, at home, on trains and planes. There was little time for my own writing or even reading favorite writers.

Alice Munro published The Moons of Jupiter and immediately won me. Over the years, her work became the highest standard I aspired to. Disclosures about her private life, revealed after her death, have tainted my esteem. But I’d never deny her unique narrative voice and the mysterious power of her story telling and ability to surprise, or describe the emotional transactions between men and women with unfaltering vision.

I loved working with authors and felt my careful input helped them write better books. But I still wanted to write my own books and the only difference between me and most authors I worked with was the courage to step forward and go for it.

Around this time, my husband and I divorced. I was now totally independent, with some savings in the bank. So far, I’d strived to meet goals set by others—my parents, husband, professors, and managers at work. I wanted to make choices that pleased myself.

I decided to jump the fence. I quit my job, and moved out the city to a quiet, quaint village on the Long Island Sound. I found an agent and submitted work under my maiden name which former colleagues didn’t recognize. I had to be sure I could earn a living on the strength of my work, not because someone I knew was doing me a favor.

I did earn a living, but the myriad of editorial and writing projects I took on left little time and less head space for the type of writing I wanted to do. I plodded along, working on short stories, elated by another tiny but positive note from another editor at The New Yorker. She liked one of my stories but said it read “more like a section of novel.” That sounded like advice. I immediately set about expanding the tale of a waitress who finds a baby in a laundromat.

My writing lessons at that time came mainly from Anne Tyler. Especially Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant and The Accidental Tourist. I gravitated to her eccentric but believable characters, the deep but softly delivered wisdom about relationships, especially family ties. I was also fascinated by Don DeLillio’s White Noise, and the beautiful short stories of Grace Paley. All those authors and books found a place on the special shelf.

A few years passed. I turned out a stack of middle grade fiction, romance novels and YA nonfiction, most under pen names. But I was not getting from A to B. Feeling defeated I slunk back into editorial work.

I was marrying again and we’d bought a place in Brooklyn. I wanted to be responsible and hold up my end. My new plan was to work strictly nine to five and devote my spare time to “real” writing. Namely, the waitress novel which was evolving. Writers I read and studied at that time included Alice McDermott, Ann Patchet and eventually, Elizabth Strout. I’d read anything they wrote.

After my daughter was born, I was once again torn between returning to an office, or taking any sort of editorial or writing project to earn a decent salary. Of course, staying home with her and shelving my ideals…again…won. When she was about five, a lucrative project landed in my lap. I was asked to create a book series for the artist Thomas Kinkade. I knew nothing about him. There was a gallery nearby that sold his work and I took a look, later describing his style as, “the Hudson River School meets My Little Pony.”

Despite my ambivalence, I took the job and created a coastal village in New England filled with believable, likeable characters; a web of families loosely linked by a church. Random House bought it and I was hired to ghost write the books. Kinkade, or rather his corporation, supplied artwork for the cover. I don’t think he ever read any of them.

I looked at it as a job and did my best to write stories acceptable to the publisher and also, to me. The initial contract was three books. But the series last for twenty years, and twenty-six books, all toll. Cape Light won a loyal audience, and I still get messages from readers asking for more stories. If I’ve given people hours of entertainment and escape from their worries, and some insight and encouragement, that’s a good thing. Even if it’s not the thing I set out to do.

As usual, even in the midst of Cape Light, I had an alternate plan. I was determined to publish a mystery. Back to the library, where I read through stacks of books and came up with a series about a woman who inherits a restaurant and ends up solving mysteries. An editor at Pocket Books liked my writing but wanted something cozier, a mystery series that included knitting. Could I do that?

It had never crossed my mind. But back to the drawing board…and library. The Black Sheep knitters were born, and I enjoyed writing about this group of intelligent, working women, their bonds of female friendship and women’s issues. Along with creating intricate mysteries for them to solve. I liked this series enough to put my real name on it for practically the first time.

What had I been saving my real name for? Well, some literary achievement that had not happened. Yet.

The Cape Light novels ended during Covid, and the Black Sheep mystery series, as well after thirteen titles. Not much happening in publishing…or anywhere. I threw myself into a book I’d started years prior, a mystery close to my heart, set in New York City just after World War II. The main character was loosely based on my mother and her Italian-American family. From the start, I pictured a woman working for a private detective who is left alone to investigate.

I didn’t know what the mystery was, or why the P.I. disappeared. But the cornerstones were laid.

It had evolved from a simple, straightforward who-done-it, to a story with more layers and challenging themes of social injustice and feminism, set against the dynamic shifts in post war American society. I was happy and relieved to finish, feeling it was the first work I would be proud to publish without the least reservation. The best thing I’d written so far. For better or worse, my agent of ten years did not feel the same and we parted ways.

That was just the start of a long, daunting road I’d travel. Remember the college student who pulled three literary journals off a shelf and heard good news almost overnight? This attempt at getting published was just the opposite experience.

Several editors honestly loved it, but were unable to get it past an editorial board. They’re encouragement put fuel in my tank. But there were times I put it aside. Not admitting defeat but needing a rest. I got a second wind, and then a third. I started off with a fresh list of small publishers and submitted again.

Within a few weeks, I had two offers. One from Shawn Reilly Simmons at Level Best Books. Her enthusiasm made me feel as if I was hallucinating—like that guy who’s trekking across a desert and imagines an oasis? But the offer was real and the book had finally found a home.

The publication of More Than You Know, just a few days ago, has been the culmination of a long, winding journey as a writer, starting with the poems of a five year old, and over forty books written under a myriad of pen names. It was a writing lesson in persistence and willpower, and pushing forward, despite being tempting to accept that I could not hit the mark I’d aimed for. But the many mentors on my special bookshelf, from E.B. White to Jane Austen, and Walt Whitman and more insisted I’d come too damn far to give up, and urged me not to waste all those hard-won writing lessons.

More Places to Go

Donis on Facebook

Type M for Murder